Let’s start with a few depressing quotes from my interviewees:

“I get really frustrated watching the church trying to innovate”

“I just don’t see any entrepreneurial flair within the church”

“A lot of pioneers are popping out the sides. They don’t fit in the church”

“Entrepreneurship in the church would look completely alien, because it’s not like anything in the past”

“There has to be boldness. There has to be creativity. There has to be risk-taking. There has to be a willingness to try new things, some of which will fail. And that has not been the mindset”.

Oh dear. If that’s where we’re at, why bother? Might we be as well to just pack up and go home? Hopefully not, but if we’re going to address this issue properly, we need to look these statements square in the face and take them seriously, and not just dismiss them as the view of the grumblers and the disillusioned.

But how have we got to a place like this? Part of the problem is that, in the main, churches move slowly and change slowly. As the parodic refrain goes, “Like a mighty tortoise, moves the church of God. Brothers we are treading, where we’ve always trod”. One of my interviewees commented that, with pioneers, “there’s a level of passion that the incrementalism of the church doesn’t sit with”. The polity of our churches tends towards the democratic, and synods, councils, committees and church meetings are all useful mechanisms for consultation but not for innovation[1].

Alongside this, there can be strong disagreement over the nature of the issues we face, what to do about, or whether to do anything about it at all. Comments like “there was a lack of clarity around the agenda and an unwillingness to confront particular obstacles”, “there was an element of ‘rabbit in headlights’ about this in respect to change”, and “I am frustrated because it feels like there is an element of displacement going on here” don’t exactly fill you with much hope for the future.

On top of this is a specific Scottish cultural problem, found at the ‘dark side’ of Scottish cultural egalitarianism[2]. Three quotes from three different people; “The Scottish cultural ‘tall poppy syndrome’ thing that kicks off, you know, ‘who do you think you are?’”, “there is a tall poppy thing. We tend to be quite dismissive of people who are doing a good job”, and “what really puzzles me is there is something in the culture which encourages entrepreneurship, but people have to go away to do that”. And a fourth interviewee shared honestly about their own fear; “I don’t want people to say, ‘who does he think he is?’”.

So far, so depressing. Is there another side to this, one that is a bit more hopeful?

One of my more surprising findings is that churches that exercise a higher degree of control and focus over their activities and direction tends to produce more entrepreneurial activity than those that are more permissive and open about what they do. This ‘control’ also links to a culture of expectation; “if you plant a congregation, you’re expected to produce results. But you’re supported in doing that. They’re not just dropped in at the deep end”. A few people have looked somewhat longingly as the power of bishops in the Church of England, and what they are able to achieve; “the bishop is a focus of unity but also a source for protecting innovation”.

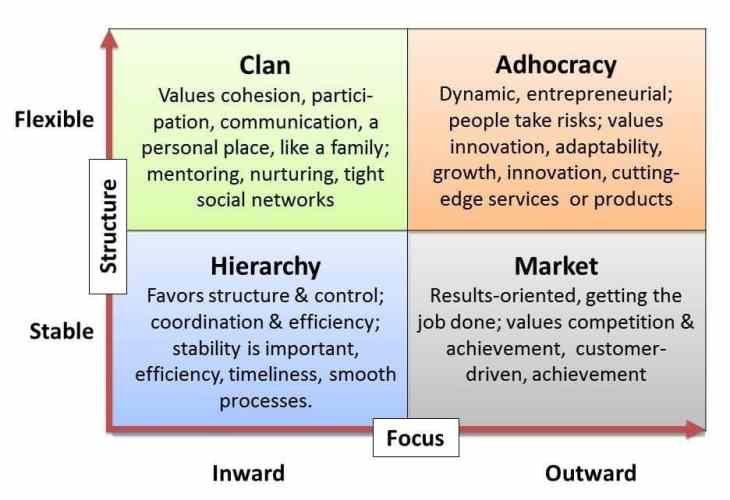

This brought to mind the Competing Values Framework, which is a useful model for thinking about different organisational cultures (even – or perhaps especially – in organisations like the Church).[3] In this model, all organisational cultures exist along two intersecting spectrums, an internal-external focus and a flexibility-stability focus. It can be rendered diagrammatically thus:

Prior to my research, I would have assumed that the Adhocracy culture would be the one that lent itself most strongly to entrepreneurial emergence (it is even listed as such in the diagram above). But my research suggests that the Market culture matters at least as much, if not more. Perhaps this is because it is more focussed and less disparate than the Adhocracy culture. But whatever the case, it is an External orientation that correlates strongly to entrepreneurial leadership, rather than an Internal one. And I suspect that many (most?) churches and denominations would recognise themselves in the Clan culture (that has certainly been the case on the several occasions when I have use this framework and its associated questionnaire with Christian organisations). Church leaders are nice people[4], and they want to care for people[5]. So that’s the kind of cultures we end up producing.

This issue of organisational culture raises the chicken-and-egg question of “Which comes first?”. Does a particular culture produce a certain kind of person, or are certain kinds of people attracted to a particular culture? As one person said to me about a network of churches they admired, “It’s a both/and. It does attract people with that sort of personality, that is prepared to take risks, but that’s reinforced with all the teaching that they do”. There’s a virtuous-circle kind of thing going on (which means that in the opposite kind of culture, you get the opposite vicious-circle kind of thing happening, where you can’t attract or produce the kind of people who will help you to break out of your stagnation and decline).

So, what do you do if you are in the ‘hindering’ culture rather than the ‘enabling’ culture? How do you inculcate new ways of thinking, behaving and being? It’s a tricky one, but at the very least the findings that I shared previously need to be pursued – it’s about giving permission, it’s finding those ready to have a go at something, and it’s about inculcating tenacity. As one church leader told me what he would say to potential pioneers and entrepreneurs, “there’s going to be an awful lot of stuff you have to suck up. Here’s my phone number. When you’re totally fed up, phone me and I’ll try and encourage you to keep going”. So that might be where you need to start. But it’s about more than a few techniques. It’s about the culture of your church or your organisation. With reference to the same network mentioned above, “other churches have seen it, have tried to copy the practices, but haven’t produced pioneers … they see it working, they then apply it, and then perceive that it doesn’t work”. So it’s not about techniques, or even about your strategy. It’s about your culture. Remember, “culture eats strategy for breakfast“.

[1] Maybe you’re thinking of Aesop’s fable of the tortoise and hare at this point. Fine. But it’s a story, and not even one from the Bible! And my research is telling me that tortoises don’t innovate, hares do.

[2] Although, while there is evidence that Scotland thinks it is more egalitarian than England, there is less evidence that it actually is. See http://blog.whatscotlandthinks.org/2013/10/two-different-countries-scottish-and-english-attitudes-to-equality-and-europe/ and https://www.theguardian.com/uk-news/scotland-blog/2015/mar/26/three-things-the-latest-british-social-attitudes-survey-tells-us-about-scotland.

[3] KS Cameron and RE Quinn (2006), Diagnosing and Changing Organisational Culture, based on the Competing Values Framework, San Francisco,CA:Jossey-Bass

[4] Mostly.

[5] Usually.